They arrived in U.S. as children; DACA recipients now fear changes

BY ELIZABETH WONG BARNSTEAD, THE WESTERN KENTUCKY CATHOLIC

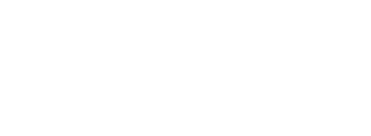

Armando Zamarripa was only a few months old when his mother faced a painful decision: choosing which of her two sons to take with her to the United States.

“She had to pick between bringing me or him… it’s hard to take kids with you across the border,” said Zamarripa in a Jan. 5, 2018 interview with The Western Kentucky Catholic. “And she thought it would be easier with me.”

He said his mother carried him across the border from Mexico to the U.S., where they then traveled to Kentucky: “My mom brought me here to give me the opportunity for a better life.”

“So I’ve been living in the United States since I was a baby,” said Zamarripa, who is 17 and a senior at Henderson County High School. He belongs to Holy Name of Jesus Parish in Henderson.

Zamarripa is one of approximately 800,000 individuals living in the U.S. who is covered by DACA – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals – a program announced by the Secretary of Homeland Security in 2012.

Recent changes, however, have made DACA recipients’ situations precarious.

DACA was made available to certain undocumented individuals who were brought to the U.S. under the age of 16. After paying a fee, recipients received a permit that was renewable every two years, and could qualify for employment authorization, a Social Security number and a driver’s license.

DACA did not create a pathway for citizenship; its purpose was merely to prevent recipients from deportation.

In September 2017, President Donald Trump’s administration announced it would end DACA in March 2018 if Congress does not come up with its own solution.

While legislators debate immigration reform especially in light of DACA, people covered by DACA are now wondering what it means for their daily lives.

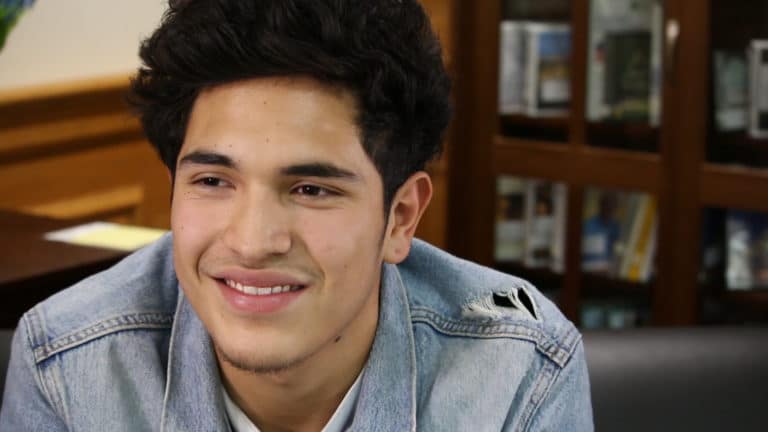

This impacts the family of Christian Rosas, who left Mexico at age 10 with his mother, hoping for a more secure future in the U.S.

“We came in 2004, crossed the desert, walked eight hours through the whole night,” said Rosas, who also belongs to Holy Name of Jesus Parish.

Now in his 20s, Rosas is the main provider for his household which includes himself, his mother, and two younger brothers.

His DACA work permit expires this November. This would mean he would no longer qualify for a driver’s license, nor would he be able to continue his current job.

“First of all it would affect my mom because she doesn’t know how to drive,” said Rosas. “She would have difficulties going to work… she would have a hard time taking my brothers to school or to doctors’ appointments or anywhere.”

Rosas explained that by applying to DACA, the Department of Homeland Security “already has all of my information, and where I live, so I would be scared that they could just come in the door and say ‘you have to go back.’”

Susan Montalvo-Gesser, managing attorney of Kentucky Legal Aid and a parishioner of SS. Joseph and Paul Parish in Owensboro, said that these situations “are all over our diocese.”

These young people “have Kentucky accents; they were baptized in our parishes; they made First Communion with our kids,” she said.

Montalvo-Gesser said many people ask why these individuals cannot just apply for citizenship, since they clearly wish to remain and contribute to society.

“People think it’s like getting a ticket to get into a baseball game,” she said. “Right now, there’s no path for them to apply for citizenship.”

One option in the works is the Dream Act of 2017, a bipartisan bill which would provide DACA recipients with a direct route to citizenship by pursuing higher education, entering the U.S. workforce or enlisting in the military. It was introduced in July 2017.

Montalvo-Gesser said steps can be taken in local Catholic communities to welcome immigrants.

“Don’t treat them differently,” she said. “We worship the same God; we go to the same church.”

She also advised paying attention to vocabulary that is in line with Catholic social teaching; for instance, though someone may be in the U.S. illegally, “no person is ‘illegal,’” she said.

In offering legal aid clinics for the local immigrant community, Montalvo-Gesser said she has been inspired by “how much they love this place and want to be a part of it.”

“Some of the best stories about America come from people who weren’t even born in America,” she said.

Laura Clarke contributed to this story.

Originally printed in the February 2018 issue of The Western Kentucky Catholic.

Copyright © 2018 Diocese of Owensboro/The Western Kentucky Catholic

Listen to Their Stories

Armando and Christian share their stories in January’s Across the Diocese.

National Catholic Call-In Day: February 26, 2018

The Diocese of Owensboro joins the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in participating in a national Catholic Call-In Day to Congress (Feb. 26, 2018), expressing support for Dreamers and asking for them to find a solution before the March 5 deadline that President Trump set for ending DACA – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. To learn more, visit owensborodiocese.org/dreamers.